Blueys in the Bush

Short notes on the distribution and habitat of Tiliqua and Cyclodomorphus in New South Wales, Australia.

Steven Sass1,2

1nghenvironmental, PO Box 470, Bega NSW. e steven@nghenvironmental.com.au

2Ecology and Biodiversity Group,

Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Thurgoona NSW.

The ‘blue tongue’ lizards are regarded as one of the most iconic reptile species in Australia (Koenig et al., 2001). The Tiliqua are a familiar genus whose members are often encountered in suburbia and along country roads, while the Cyclodomorphus are shy and secretive and rarely observed. ‘Blue tongues’ can be found in almost every part of the continent, with the state of New South Wales being no exception.

This paper provides some short notes on the distribution and habitat of Tiliqua and Cyclodomorphus that are known to occur within New South Wales.

Tiliqua

Of the six species of Tiliqua that occur in Australia, five of these are known to occur in NSW. The Pygmy Blue-tongue Tiliqua adelaidensis occurs in South Australia (Armstrong and Reid, 1992). A sub-species of the Eastern Blue-tongue, the Northern Blue-tongue Tiliqua scincoides intermedia, is found across northern Queensland, Northern Territory and Western Australia (Wilson and Swan, 2008).

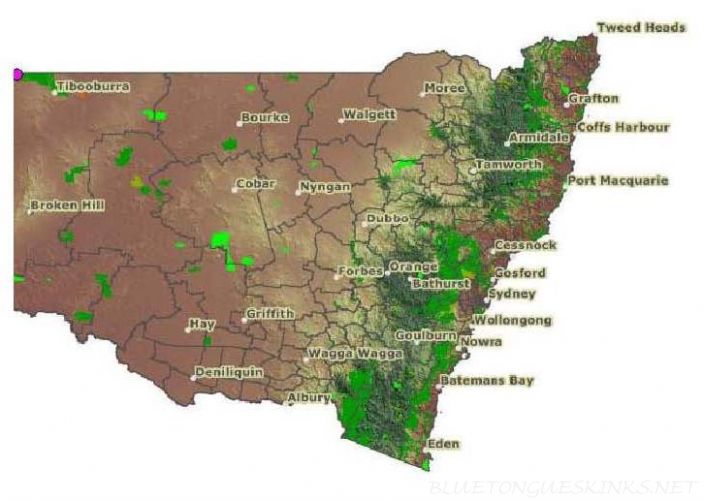

Tiliqua multifasciata

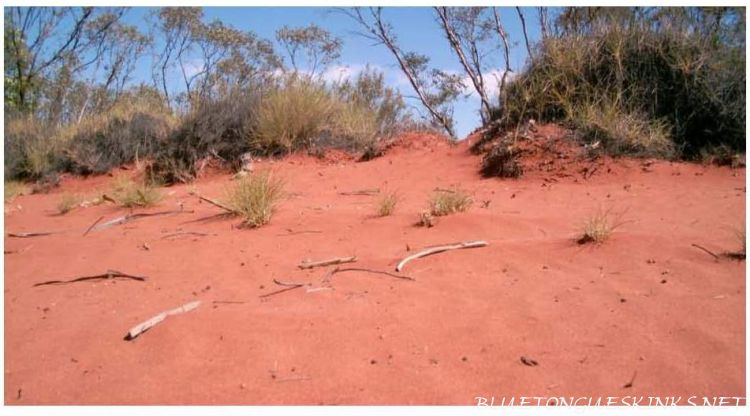

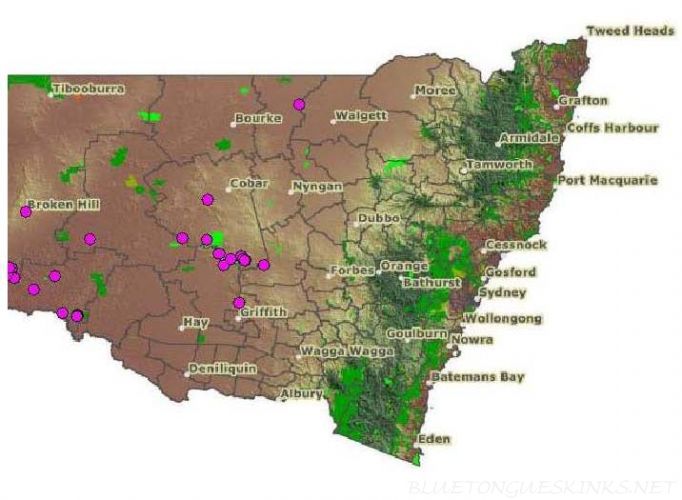

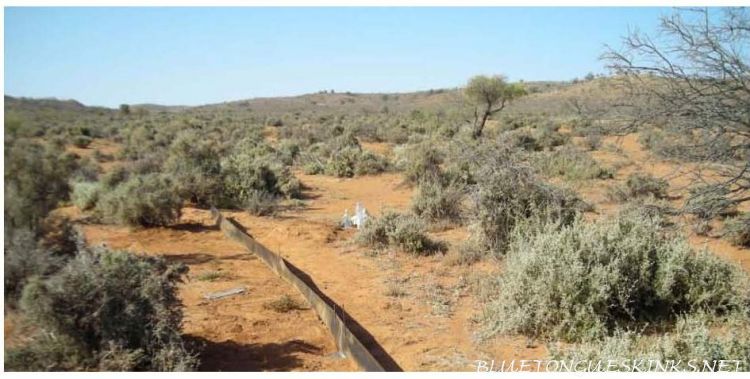

The Centralian Blue tongue is known only to occur in NSW within Sturt National Park (Swan et al., 2004; DECC, 2008a) (Figure 1). The species has been recorded within spinifex grasslands in sandy areas (Swan et al., 2004) (Plate 1). In other parts of its range outside of NSW, the species has also been found where spinifex occurs on stony ground (Fyfe, 1983; Wilson and Swan, 2008). It is this habitat specificity that resulted in the species listed as Vulnerable under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (DECC, 2008b).

Figure 1: Records of Centralian Blue-tongue in NSW (pink dot) (DECC, 2008a).

Plate 1: Spinifex/Sand dune habitat in western NSW.

Tiliqua nigrolutea

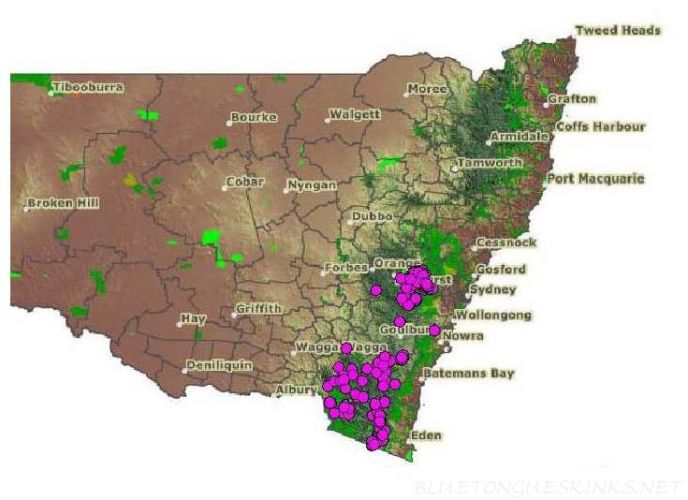

The Blotched Blue-tongue is found across two disjunct populations in NSW; the Blue Mountains region and the Southern Highlands (Swan et al., 2004; Sass et al., 2007; DECC, 2008a) (Figure 2). In the Blue Mountains, records are common around the towns of Katoomba and Oberon while in the Southern Tablelands, records exist from Goulburn in the north (pers.obs) to Cooma and beyond in the south. Modelling of the potential distribution of Blotched Blue tongue using climatic data predicted a much wider distribution than existing museum records suggest (Hancock and Thompson, 1997). However, the absence of these records is likely to indicate that other factors such as dispersal and long-term isolation of potential habitat are limiting the distribution of this species rather than climate alone.

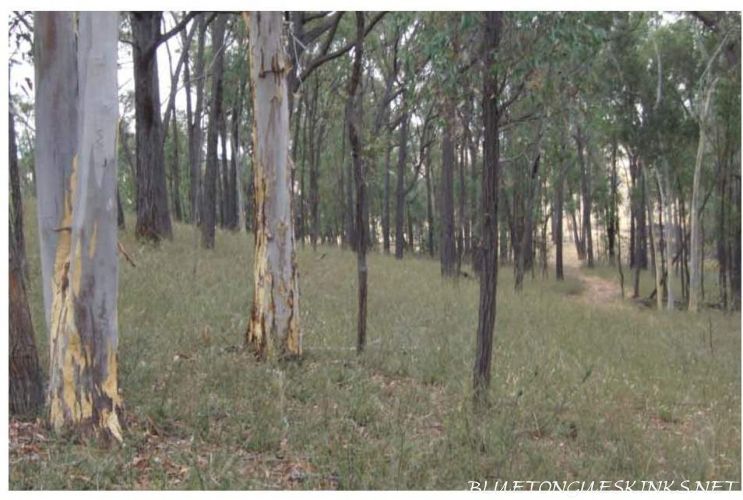

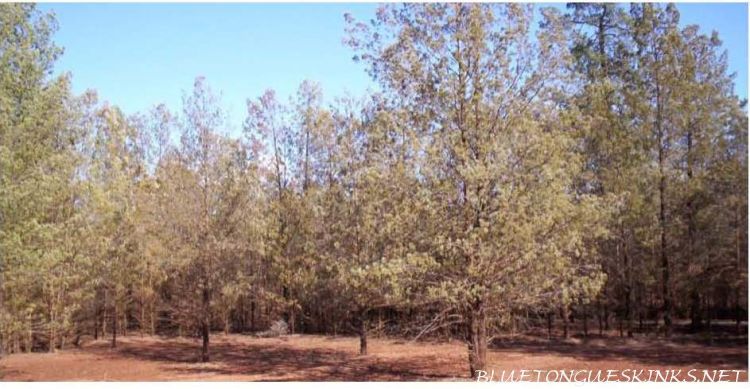

Blotched Blue-tongue occurs across a variety of habitats such as dry sclerophyll forest (Plate 2), eucalypt woodland (Plate 3), alpine woodland (Plate 18) and grassland (Plate 4) (Sass et al., 2007; Shea, 1982; Swan et al., 2004; Hancock and Thompson, 1997).

Plate 2: Dry sclerophyll forest in the NSW Southern Tablelands (Photo: S.Sass).

Plate 3: Eucalypt woodland in the NSW Southern Tablelands (Photo: S.Sass).

Plate 4: Native grassland in the NSW Southern Tablelands (Photo: S.Sass).

Figure 2: Records of Blotched Blue-tongue in NSW (pink dots)(DECC, 2008a).

Tiliqua occipitalis

The Western Blue tongue is found in arid and semi-arid areas of Australia (Fyfe, 1983; Swan et al., 2004; Sass, 2006). Most records in NSW are within the structurally complex mallee/spinifex habitat (Plate 5). However, they are also known to occur within chenopod shrublands (Plate 6). The habitat specificity of this species combined with the likelihood that their distribution is suspected to have been reduced due to habitat degradation and/or removal, resulted in the Western Blue tongue being listed as Vulnerable under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (DECC, 2008b).

This species has been most recorded in Yathong, Nombinnie and Round Hill Nature Reserves in central western NSW, around Broken Hill and in the south-western corner of NSW around Mallee Cliffs National Park, Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area and Tarawi Nature Reserve (Swan et al., 2004) (DECC, 2008a) (Figure 3).

Plate 5: Mallee/spinifex habitat in western NSW (Photo: S.Sass).

Figure 3: Records of Western Blue-tongue in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Plate 6: Chenopod shrublands in western NSW (Photo: S.Sass)

Plate 7: Acacia shrubland habitat in western NSW (Photo: S. Sass).

Tiliqua rugosa aspera

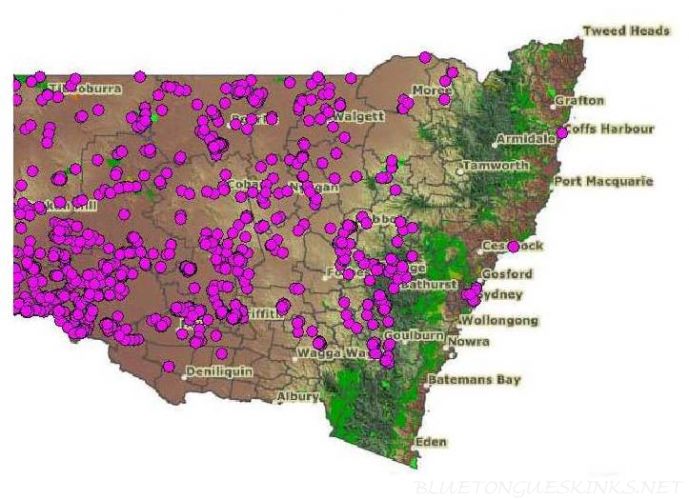

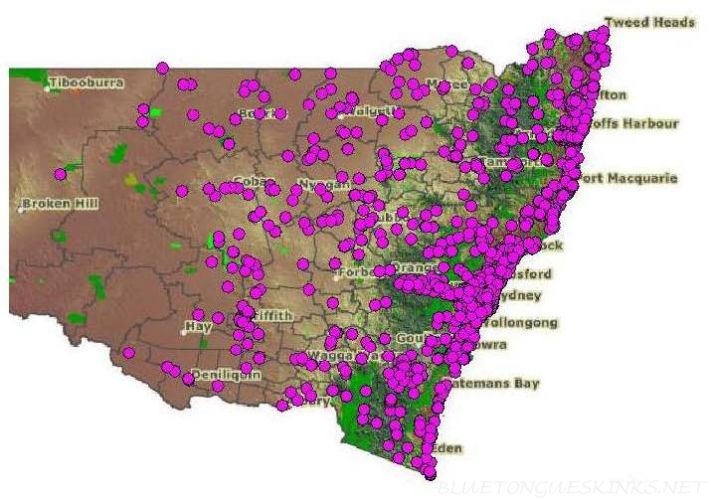

The Shingleback is found across a variety of habitats and is regarded as the most widespread Tiliqua in NSW. Generally, this species is found west of the Great Dividing Range (DECC, 2008a) (Figure 4). However, Shinglebacks are also found on the Great Dividing Range in several locales including the Yass/Goulburn/ACT area and near Tamworth in the north. Figure 4 also reveals some coastal records particularly around Sydney but these are probably escapees or deliberate dumping of captive animals.

The habitat of this species is variable across the state according to vegetation distribution. Individuals occurring along the Great Dividing Range are generally found within eucalypt woodlands (Plate 3), native grasslands (Plate 4) and farming areas (Swan et al., 2004). The western plains of NSW appear to be the stronghold for this species, where they are most commonly encountered in wide variety of habitats ranging from mallee and acacia shrublands (Plate 5, 7), eucalypt woodlands (Plate 8), cypress-pine woodlands (Plate 9) and chenopod shrublands (Plate 6). Henle (1989) identifies that Shinglebacks are largely absent from expansive floodplains even when these features have been dry for many years (Henle, 1989). However, recent surveys undertaken along the floodplains of the Darling River, in far-western NSW, revealed Shinglebacks were the most common reptile species within black-box woodlands (Plate 10), a riparian-floodplain community of the Darling River (Sass, S., in prep).

It has been reported that Shinglebacks are rare on stony and rocky hills throughout their range (Hitz & Henle, 2004). However, surveys across such habitat in the Barrier Ranges near Broken Hill found that the species were often encountered (NGHEnvironmental, 2008) suggesting that these habitats could be used according to resource availability across different seasons and possibly years.

Plate 8: Eucalypt woodland habitat in western NSW (Photo: S.Sass).

Plate 9: Cypress pine woodland habitat in western NSW (Photo: S.Sass).

Figure 4: Records of Shingleback in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Plate 10: Black box eucalypt woodland on the Darling River Floodplain (Photo: S.Sass).

Plate 11: Rocky hills near Broken Hill where Shinglebacks have been recorded (Photo: S.Sass).

Tiliqua s.scincoides

The Eastern blue tongue is the only species of Tiliqua naturally found within the NSW capital, Sydney where it can be found living and breeding within bushland and appears equally at home in backyard gardens (Koenig et al., 2001; Koenig et al., 2002). This defies the trend of many reptiles, which have retreated into pockets of remnant bushland which are now absent across many parts of Sydney (Koenig et al., 2002).

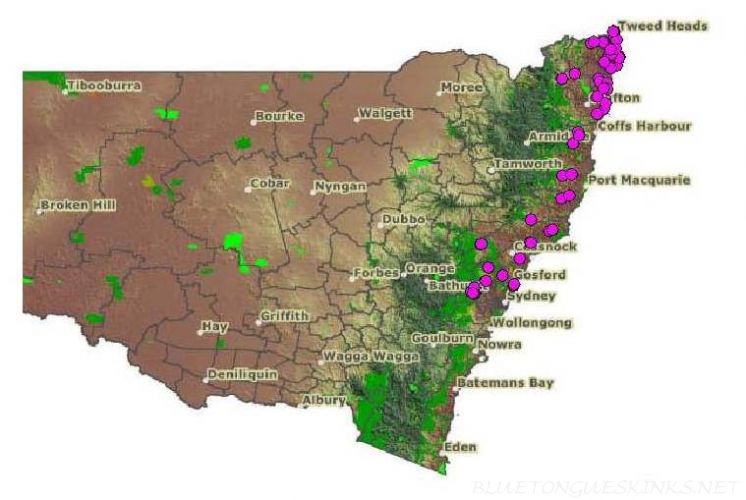

Most regard the natural distribution of the species to extend from the NSW coast westward to the Cobar Peneplain bioregion (Hancock and Thompson, 1997) where it is sporadically recorded within bimble box-pine woodlands and rocky hills (Sass and Swan, submitted). In recent years, individual Eastern blue tongue have also been found further west, including within the Paroo-Darling National Park (Swan, G., unpubl.data) and the Barrier Ranges (Sass and Swan, In prep.; DECC, 2008a) (Figure 5). Scattered populations in western NSW are likely the result of wetter periods in geological time reflecting a wider distribution with only relict populations remaining since the aridity of Australia commenced. One such example is the small population of Eastern Blue-tongue that is known from a rocky outcrop and gorge system in the arid zone within north-western South Australia (Johnston, 1992).

Eastern Blue-tongue are found across dry sclerophyll forest (Plate 2), eucalypt woodland (Plate 3) and suburban parks and gardens (Plate 12). Across the Cobar Peneplain, they are commonly encountered amongst eucalypt woodlands dominated by bimble box Eucalyptus populnea spp. Bimblii and red box Eucalyptus intertexta (Plate 8).

Figure 5: Records of Eastern Blue-tongue in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Plate 12: Typical surburban backyard on the NSW south coast (Photo: H.Sass).

Cyclodomorphus

Of the nine species of Cyclodomorphus in Australia, five species are known to occur in NSW. Generally, the distribution of these five species does not overlap, with the exception of a very small overlap of two species on the NSW central coast (Swan et al., 2004).

Cyclodomorphus gerrardii

Pink-tongued skinks are found along the east coast of NSW, from around the Sydney region to the Queensland border and beyond (Wilson and Swan, 2008). Most records in NSW are in the far north coast regions between Coffs Harbour and Lismore, and in the Blue Mountains region (DECC, 2008a) (Figure 6). The species prefers a humid environment such as those found within rainforests (Plate 13) and wet sclerophyll forests (Plate 14) of the Great Dividing Range and adjacent coastal plains.

This species is most commonly encountered in their natural habitats after rain events on warm evenings hunting snails and slugs (Wilson and Swan, 2008).

Plate 13: Rainforest habitat on the Great Dividing Range (Photo: L.Sass).

Plate 14: Wet sclerophyll forest habitat in northern NSW (Photo: S.Sass)

Figure 6: Records of Pink-tongue lizard in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Cyclodormophus melanops elongatus

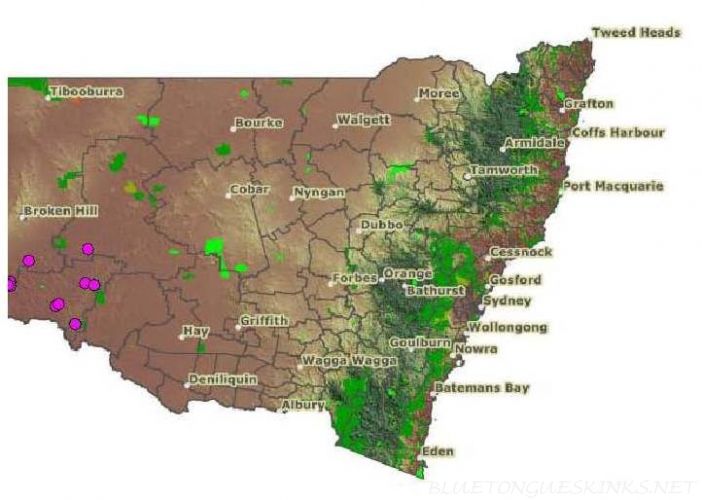

Southern Spinifex Slender Blue-tongues are a spinifex obligate species that has a highly restricted distribution in NSW (Shea, 2004a). It has been recorded from around Coombah Station, between Mildura and Broken Hill, Tarawi Nature Reserve, Scotia Sanctuary and the Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area (DECC, 2008a) (Figure 7).

In all records, the species has been found in a habitat dominated by spinifex grass (Triodia spp.) on sand dunes (Plate 1 & 5). The recent discovery of an undescribed vegetation community dominated by spinifex grass growing on rocky ground (Plate 15) (Benson and Sass, 2008) lead to detection of this species north-west of Broken Hill where it was not previously known or predicted to occur (Sass and Swan, In prep.).

The species is listed as Endangered under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (DECC, 2008b). This was largely due to the alteration of natural fire regimes, in association with grazing, which is likely to directly affect their habitat (DECC, 2008b). These factors are likely to threaten the long-term survival of this species such as it could become extinct (DECC, 2008b).

The species is very secretive, and is rarely encountered. Consequently, little is known of the ecology of the Southern Spinifex Slender Blue-tongue and further research is needed to aid in the recovery of this species including land management.

Searches of spinifex grass clumps often reveal the presence of this species and they are conducive to capture within pitfall and funnel traps. Southern Spinifex Slender Blue-tongues can also be observed foraging during early morning walking transects and by spotlighting on warm nights in suitable habitat. Nevertheless, searches of spinifex grass and trapping is the most reliable method of detection.

Plate 15: Spinifex on rocky ground north-west of Broken Hill, NSW (Photo: S.Sass)

Figure 7: Records of Southern Spinifex Slender Blue-tongues in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Cyclodomorphus michaeli

The Northern She-oak Skink has a patchy distribution across NSW with populations known from the New England, Low North Coast, Central Coast, Blue Mountains, Illawarra and Far South Coast regions (Swan et al., 2004; Shea, 2004b; DECC, 2008a) (Figure 8).

Throughout their range, the species can be found within a variety of habitats such as wet and dry sclerophyll forests (Plate 13 & 2), rainforests (Plate 13) and woodlands with a grassy understorey (Plate 3) (Shea, 2004b; Wilson and Swan, 2008; Swan et al., 2004). However, the species appears likely to be most encountered within sandy coastal heaths (Plate 16) and sandstone heaths (Plate 17) of the coastal plain and escarpment areas. In many areas, the species is also found around water sources such as swamps, creeks and wetlands within these habitats.

Secretive by nature, Northern She-oak skinks are best observed in the field early morning when individuals can be seen basking adjacent to dense cover. They can also be located by searching large flat objects such as corrugated iron, carpet sheets and other discarded rubbish where animals shelter underneath (Shea, 2004b).

Plate 16: Coastal heath on the NSW far south coast. (Photo: S.Sass).

Figure 8: Records of Northern She-oak Skink in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Plate 17: Sandstone heath on the escarpment on the NSW mid south coast (Photo: S.Sass).

Cyclodomorphus praealtus

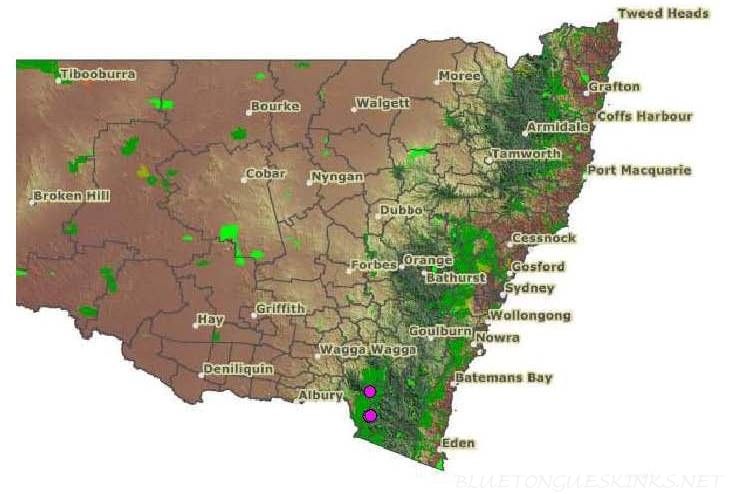

The Alpine She-oak skink is found within the alpine regions of NSW (Shea, 2004b; Clemann and Nelson, 2005; DECC, 2008a) (Figure 9). While little is known on the ecology of the species, it has only been recorded above 1500m elevation and typically within alpine grasslands (Plate 4) and woodlands (Plate 18) (Shea, 2004b; Swan et al., 2004).

The secretive nature of the species has meant that observation in the field is difficult. However, Swan, Shea and Sadlier (2004) reveal that Alpine She-oak skinks may occasionally be seen basking on the top of grass tussocks. Clemann and Nelson (2005) provide detail on the monitoring of populations in the Victorian Alpine region using artificial ground covers such as roof tiles, which they shelter beneath, allowing easier detection of the species.

Figure 9: Records of Alpine She-oak Skink in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Plate 18: Alpine woodland in the NSW Snowy Mountains (Photo: S.Sass).

Cyclodomorphus venustus

The Saltbush Slender Blue-tongue is confined to the far north-western corner of NSW, where they have only been recorded within Sturt National Park (DECC, 2008a, Swan et. al., 2004) (Figure 10).

Listed as Endangered under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (DECC, 2008b), the ecology of this species is largely unknown. Swan, Shea and Sadlier (2004) describe their habitat as cracking grey soils in floodways with the species occasionally being found on stony ground. It has also been recorded within coastal samphire and saltbush habitats (Shea, 2004a). Considering the endangered species status of this species in NSW, further ecological study should be given high priority.

Figure 10: Records of Saltbush Slender Blue-tongue in NSW (pink dots) (DECC, 2008a).

Acknowledgements

Without my beautiful wife Linda, and our four children, Amy, Zoe, Holly and Joshua, and their support of my herpetological interests, this paper would not have been possible. I would also like to thank Zach from BlueTongueSkinks.NET for inspiring me to collate this information.

References

ARMSTRONG, G., and J. REID. 1992. The rediscovery of the Adelaide pygmy bluetongue, Tiliqua adelaidensis (Peters, 1863). Herpetofauna. 22:3-6.

BENSON, J. S., and S. SASS. 2008. NSW Vegetation Classification: ID 359: Porcupine Grass - Red Mallee - Gum Coolabah hummock grassland / low sparse woodland on metamorphic ranges on the Barrier Range, Broken Hill Complex Bioregion. Unpublished report by Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney.

CLEMANN, N., and J. NELSON. 2005. Developing a survey and monitoring technique for the threatened Alpine She-oak Skink Cyclodomorphus praealtus – artificial cover object deployment and initial survey. Report prepared for North-east Catchment Management Authority.

DECC. 2008a. NSW Atlas of Wildlife Database.

—. 2008b. Threatened species, populations and ecological communities of NSW. Department of Environment & Climate Change, Hurstville, N.S.W. www.threatenedspecies.environment.nsw.gov.au.

FYFE, G. 1983. Some notes on sympatry between Tiliqua occipitalis and Tiliqua multifasciata in the Ayers Rock Region and their associations with Aboriginal people of the area. Herpetofauna. 15:18-19.

HANCOCK, L. J., and M. B. THOMPSON. 1997. Distributional limits of eastern blue tongue lizards Tiliqua scincoides, blotched blue tongue lizards T.nigrolutea and shingleback lizards T.rugosa (Gray) in New South Wales. Australian Zoologist. 30:340-345.

HENLE, K. 1989. Ecological segregation in a Assemblage of Diurnal lizards in arid Australia. Acta Ecologica. 10:19-35.

HITZ, R and K. HENLE, 2004. The biology of Tiliqua rugosa In: Blue-tongued skinks: Contributions to Tiliqua and Cyclodormophus. R. Hitz, G. Shea, A. Hauschild, K. Henle, and H. Werning (eds.). Matthias Schmidt Publications.

JOHNSTON, G. R. 1992. Relictual population of Tiliqua scincoides (Sauria:Scincidae) in north-western South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 116:149-150.

KOENIG, J., R. SHINE, and G. SHEA. 2001. The ecology of an Australian reptile icon: how do blue-tongued lizards (Tiliqua scincoides) survive in suburbia? Wildlife Research. 28:215-227.

—. 2002. The dangers of life in the city : Patterns of activity, injury and mortality in suburban lizards (Tiliqua scincoides). Journal of Herpetology. 36:62-68.

NGHENVIRONMENTAL. 2008. Proposed development of Stage 1 Silverton Wind Farm, far western NSW: Biodiversity Assessment. Report prepared by nghenvironmental for Silverton Wind Farm Developments.

SASS, S. 2006. Reptile fauna of Nombinnie Nature Reserve and State Conservation Area, western NSW. Australian Zoologist. 33:511-518.

SASS, S., In prep. Reptile surveys of the Lower Murray Darling Catchment in far south-western NSW.

SASS, S., and G. SWAN. In prep. Additions to the reptile fauna of the Broken Hill Bioregion.

—. submitted. The herpetofauna of the bimble box-pine woodlands of the Cobar Peneplain Bioregion. Herpetofauna.

SASS, S., D. M. WATSON, and M. HERRING. 2007. A range extension for the blotched blue tongue skink (Tiliqua nigrolutea) (Scincidae) and implications for its future survival. Herpetofauna. 37:21-25.

SHEA, G. 1982. Observations on some members of the genus Tiliqua. Herpetofauna. 13:18-20.

—. 2004a. The Cyclodomorphus branchialis complex. In: Blue-tongued skinks: Contributions to Tiliqua and Cyclodormophus. R. Hitz, G. Shea, A. Hauschild, K. Henle, and H. Werning (eds.). Matthias Schmidt Publications.

—. 2004b. Sheoak skinks (Cyclodomorphus casuarinae complex). In: Blue-tongued skinks: Contributions to Tiliqua and Cyclodomorphus. R. Hitz, G. Shea, A. Hauschild, K. Henle, and H. Werning (eds.). Matthias Schmidt Publications.

SWAN, G., G. SHEA, and R. SADLIER. 2004. Field guide to the reptiles of New South Wales. Reed New Holland, Sydney.

WILSON, S., and G. SWAN. 2008. A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia, 2nd edition. Reed New Holland, Sydney.

®

®

®

®